“Bet you’ve all got a story

You're just aching to tell.

Haven't we thrown our coinage

Down the wishing well?”

~ Bill Mallonee and the Vigilantes of Love, Doublecure

ask foundational questions

The year which is about to close out generates as much comment as emotion. During a recent radio interview for which the topic was journaling and letter writing, I talked about eagerly looking forward to the privilege of reflecting back about this current crisis in retrospect. This is to say when this plague is past. For the time being, and much of the last 10 months, I’ve continued writing, teaching remotely, and encouraging others to write their stories. Every person has volumes. Throughout the year, I’ve thankfully continued working at my employment- humble as it is- and in as much isolation as possible. Interspersed with my duties, whether on-site or in my apartment, my daily journaling also continues. I’ve noticed my written entries are much more detailed about the mundane than before. It’s surely related to the confinements of pandemic life. Although I’m staying afloat, it’s a desolate voyage. Perching to write last night, it amazed me that even amidst this time of exile there is still plenty to write about.

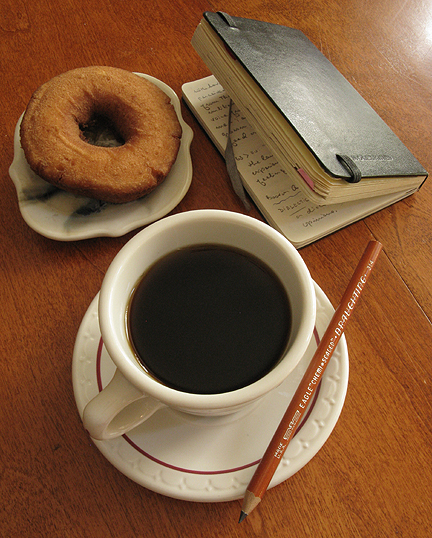

An old and affectionate ballad asks the pleasantly rhetorical question, “tell me why the stars do shine; tell me why the ivy twines?” The listener surely knows the answer, as these lines state what is mutually obvious, as sure as the ocean is blue. “Tell me,” I asked myself, “why do I write?” Well, the ocean is blue, the ivy twines; and as surely as I live and breathe, I write. Being in a much more pared-down life than before last March, the creature comforts are few and modest. But I make sure to write: this is a continuum that is always enjoyable, consoling, and vital. Neither a smoker nor a drinker, I do keep myself in good writing materials and strong coffee. These rank high among provisions. Especially now. Living and writing inextricably go together.

As I scribe my thoughts these days, usually between tasks, it is evident to me how trivial things are magnified while the wider world seems diminished. With all the necessary hygienic precautions and rules, there are no longer any spontaneous errands as before. Walks to the post office and grocery store trips have become equipped expeditions. What can’t be done or visited outnumbers what can be done or visited. At the same time, current events are brought very close- with scant positive news. Perceptions about proximity, distance, and time have been altered. All the more, writing is crucial as a balancing and restorative ingredient to my days. There is the action itself of physically setting down words on paper by hand, untethered from electronic media- and then there are the reasons for doing so. As with any creative art there are the physical actions of making, along with created content, and the work’s significance. It’s easy to take these things for granted, having committed to writing long ago (and photography much longer ago). Part of my stock-taking at the end of this difficult year is writing about why I write.

the invisible hand of providence

An easy and not altogether inaccurate answer for why I write is to say, “because I have plenty to say but I don’t wish to be tedious to those who know me.” Fine enough, though it isn’t really why I write. A person makes a mark on a page (or sculpts, composes, et cetera) in response to inner impulses strong enough to take some coordinated action. Indeed, the context for creative output is highly individualized. Throughout the decade during which I taught photography, I would say to the class that a photo image is the result of many intuitive decisions by the photographer. Such factors include vantage points, camera settings, composing what one has decided to include in the viewfinder, lighting, to name a few- and it all happens in fractions of seconds. The intentions behind the imagery are equally unique to the creative person. When I teach philosophy, I’m sure to point out the concepts of being and meaning as central to very many foundational questions.

In the spirit of the Advent season, I’m remembering how I’ve referred students to Blaise Pascal as having been solidly aware of the invisible hand of Divine providence. Agreeing with Pascal about this point, as well as that of openness to the serendipitous, I’ve learned not to lean too much on contrivance. The nature of discovery is surprise. Years ago while in art college, I strongly felt the need to read the Bible- in the vernacular. As a child in my religious instruction, I had to translate Hebrew into English; I wasn’t very good at it, and the reading was not smooth. With the High Holidays in season and feeling rather desolate, I went to the public library and borrowed a King James translation. Reading at night, after my schoolwork, I found all the familiar places and people from my childhood studies- but in refreshingly fluid English (even if it was rather Elizabethan).

Everything was linking together between ancient history, the traditions I had learned and practiced, and all the fascinating personalities. Then I arrived at a threshold in the form of a blank page and turned it, finding something I had never seen before, the New Testament. Suddenly the names were not familiar, but I continued reading. The words and events were compelling, haunting, and sweet to me. I felt the Spirit very naturally taking root, and what followed after some time was the strength of the message forcing the expansion of my ancestral religious perimeters. Embracing the gospel eventually ostracized me from my community and led to some extremely difficult years of rejection and alienation. Looking back, it is astonishing how I did not break under the strain. An old soul with a new faith. Studies, work ethics, new friends, a few great mentors, and opened spiritual horizons were just enough to start gathering some momentum for the long haul. Surely many ruts in the road; it’s never been easy, but such is the pilgrimage of trust. But the Rabbi of Nazareth taught that hard times are inevitable, yet at the same time wise words will providentially take shape from within: “By your perseverance you will gain your soul.”* I write because an unusual, irrepressible, and enduring message has been given to me.

living for the emergence

Advent represents as much about manifestation as about anticipation. The waiting is not passive. As with my native traditions, the observance lends itself to merging the historic and the symbolic. At the same time the defining spirit is a looking-forward, emphasized at the darkest stretch of the year. The turning of the season offers a chance to be inspired by the sheer passage of time, by the potential for transformation. Although journal writing is often the place for looking back to make sense of what was, and reflecting upon what is, the musing becomes an arena for ambition. In this sense, writing is aspiring. Just as I keep telling myself to keep on going while gaining context, I’m also writing ahead. The lines of my connected script date back to my first cursive loops at Public School Number 13, in New York City. (I’ve actually had the honor of visiting with the current and retired school principals at P.S. 13- even reading to them from my journal. It was a chance to express my gratitude, speaking this time as an adult with fellow adults- educators all.) Centuries before personal journal writing was popular, Quakers of all ages- women and men- were writing their reflections and impressions in diaries. Many of these journals survive to this day and are fascinating to read. The travels, perils, interactions, meditations, reminiscences, testimonies, and personal convictions represent the context of these driven individuals. Early on, Quakers believed their journals were continuations of the biblical book of the Acts of the Apostles. Good reading lightens the darkness, and so does upholding the writing torch. My inked and graphite loops and jots twine like the ivy, page after volume. And my written steps will find their way through this crucible of isolated exile when the storm passes by.

________________________

* Luke 21:19