“Even so, we also should walk in newness of life.”

~ Romans 6:4

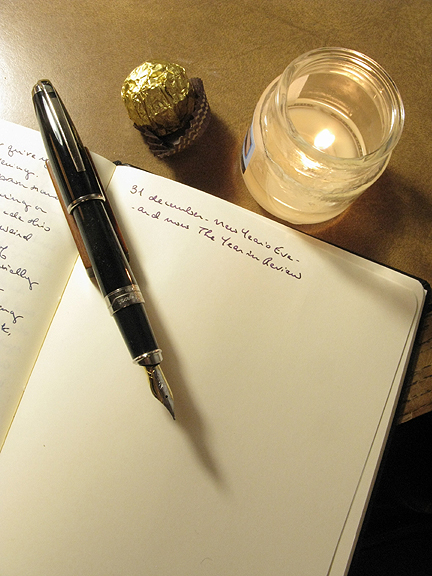

My voyage with journaling began in July 1994. Later on, graduate school caused my written entries to be regrettably intermittent. After 2000 I came to depend upon daily documentation and reflection, and the practice continues to this day. Throughout my years of writing, I’ve used the days leading up to New Year’s Eve to create retrospective “year in review” summaries. At first, I made the lengthy journal entries into Time Magazine- style features, as in “the year that was.” After a few years, these summaries became something I fashioned into several days of shorter journal entries, giving equal treatment both to events and to impressions. Without writing, telling the months and years apart would be even more difficult and surely blurred. The covid era surely represents this. It’s a snowball of largely dissimilar months, whose grip set in by the Ides of March 2020. Since then, living has been amidst minefields and restrictions. Thinking back to the world before that date, I remind myself that “everything was at least two years ago.” In keeping with my own custom, I’ve begun gathering my handwritten thoughts to recap the year which- if anything- feels as though it’s in Month 23. It is indeed a looking back, but always attempts at forward motion- traction or not.

The contrast is appropriate, connecting the establishing of winter and long nights with a season traditionally marked by newness. The Christmas holiday season has also long been relentlessly exploited commercially, with advertising beginning many weeks before Advent. Pandemic life has muted some of the competitive spending drives, forcing diminished budgets and smaller gatherings- if any. Yet the week between the western/Gregorian calendar Christmas and New Year’s Day continues to be a liminal span for various forms of reflection. The plague rages on. Will the coming year be an improvement over the one just past? How to look forward with anticipatory hope, in the bleak midwinter?

My self-determined directive is to continue seeking light in the darkness of these times, while trying to tangibly exemplify that light. For nearly two years, it has been impossible to travel or to even buy some weekdays off to rejuvenate. My semiannual pilgrimage retreats of many, many years have had to be compressed into a few occasional hours during a weekend so that I can continue being gainfully employed. Pushing back for the cause of spiritual health has also stretched nights into times of carved-out silence and study. Not doing this actually worsens the exhaustion. Admittedly, this is a trial that must be endured.

Newness begins with a thirst for promise, even for the haggard and worn. One recent midnight while preparing for the subsequent reveille that would return me to the same darkness, I methodically set up my coffeemaker and what I’d need to make next day’s entry as effortless as possible. Thinking of the combination of obligations and wishes while tidying my writing table, I remembered how an old friend used to call himself “a kid on Christmas morning,” and how that attitude helped him stay inspired. I wouldn’t describe myself as such, but there was something I liked about that sentiment. A soul’s renewal is as much a mystery as is the desire for newness. Do we inherently sense the hope of renewal? It is a fascinating thought how we seem to naturally find our own renewal- or at least the will to seek out our rejuvenation. Is this somehow built into our nature? I think we reflexively salvage the pieces we can find of our existence. The recent devastating natural disasters remind us of this. Victims who escape with their lives are looking for remnants from their households, their histories, and where their continua left off- at the times when their worlds were interrupted so they can recommence. In the less-cataclysmic scenarios, there somehow exists a natural drive to pick up and continue on. I believe this to be more than survival instinct, but the reinforcement of the holy spirit of new life. While more than enough reasons can be enumerated to give up hope, wondering about what is actually improving in our midst, we still tend to resume our searches for better and more meaningful lives.

During this year’s holiday season, I’ve noticed myself bristling more than usual at overused Christmas songs. They brought neither comfort nor joy, even to this believer. I fled to the consolations of Telemann, Bach, and how the occasion is quietly known as the feast of the incarnation. Yes, indeed, there is the commemoration of the Nativity. Not to be lost is the parallel aspect and infusion of the Divine within all whose lives return the embrace. Incarnation manifests to an ordinary human as transformation, and the latter builds an inner strength to be grateful while bearing up against hardship. Enduring the plagues in late 14th century Holland, Gerard Groote wrote, “May it never be that tribulation produce in us a faint heart; a faint heart, confusion; and confusion, the desperation that destroys.” Ancient texts accompanying this season include the name Immanuel, which in Hebrew means God is with us. Over the years, I’ve come to reverently refer to the So Near. As I’ve learned from the monks of Weston Priory whose doxology is to the Creator, Word, and Spirit of New Life, I understand the value of finding meaning beyond overused expressions.

The current provisional journey is embedded within an incalculable pilgrimage. Trying to take stock of the good that is, of the silent graces too easily overlooked, I try to be attuned to available inspiration. What is within my reach? What don’t I know that I need to know? Are we to search for newness, or enable renewal to find us? I wonder to what extent the spirit of rekindling is based upon unseen certitudes of which we could be innately aware. Perhaps there is a balance of proportion between a person’s determination, and a providence over which there is no control. And within that sense of resoluteness, does it begin with one’s desire to give rise to renewal, or are we brought to think about it from beyond ourselves? Do I procure the lamp and illuminate it, or is the already burning light catching my attention first? Unsure of what to make of the broader ailing world, as well as my own daunting setbacks, my thoughts turn to how all of this is about endurance. The transitory present is an impermanent trial. Distances and times between now and turns in my fortunes are impossible to tell. Opportunities remain out of reach, but hope remains available. Hopefulness increases the will to endure. When St. Paul wrote about how “hope maketh not ashamed,” he wanted his readers to confidently animate conscientious faith. Newness must ever be kept in mind. And kept in mind and practice with unwavering insistence.