Sunday, September 18, 2022

Thursday, April 12, 2012

graphite archive

"I've got to feel the pencil

and see the words

at the end of the pencil."

~ William Faulkner

When work impresses itself as encouragement upon daily life, extraordinary momentum and renewed energy manifest to merge both spheres. Through the occasions during which vocation and avocation intertwine, various aspects of life provide for cross-referenced appreciation. My years in commercial photography and printing helped me to become proficient at cooking and baking. The study of history and philosophy, combined with the active pursuit of the spiritual life, inspired the practice of journaling. By writing the adventures of personal journeys and the business of the quotidian, I’m better able to perceive as an archivist.

A current project permits me to play many of my cultivated notes. Just over two years ago, I was called upon to organize, index, and preserve seventy years worth of negatives produced by a local newspaper. The publisher’s building was being emptied and the sub-basement’s contents included dozens of rusted file cabinets stuffed with photographic negatives- which were being destined for a refuse smelter. Providentially, I took on the project and the experience has been as wonderful as it has been mountainous. The collection comprises hundreds of thousands of celluloid and acetate images- an incomparable treasure trove of regional images- and I’ve already identified many thousands of places, events, institutions, and individuals.

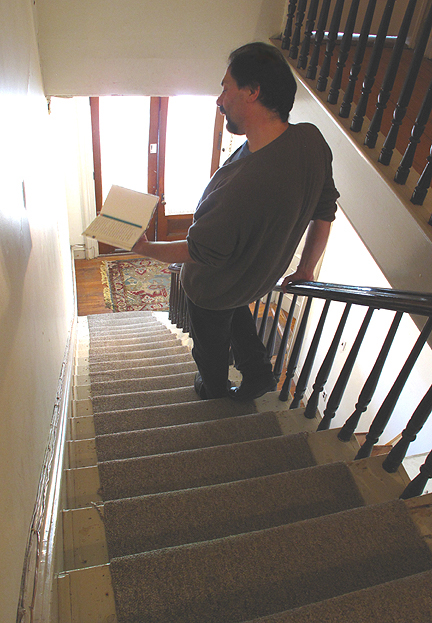

The best way to deal with this massive amount of unorganized and unindexed material has been for me to review each single piece of film, while taking a macro approach regarding descriptive depth and preservation. By doing this, I’ve been living the collection in numerous ways and at many levels. My personal memories are being bolstered by illustrative artifacts that are much older than I am, and the continuum has been blending into my own. Throughout this continuing and painstaking process, I’ve been trying to communicate the immense joy of this large project to those around me that cringe at the prospect of the daunting tedium of commandeering many hundreds of linear feet of negative images without accompanying prints. I consider it an honor and a privilege to be conserving this photographic history of my home. From the beginning, it’s been clear to me that I’ve been discovering more than mere imagery. Being a process in progress, only small portions have been made available, and a growing number of individuals have already been blessed by these thin slices of time, and new anecdotes come to me by the week. There are many stories, even now at these early stages, and I try to write as many as possible in my journal.

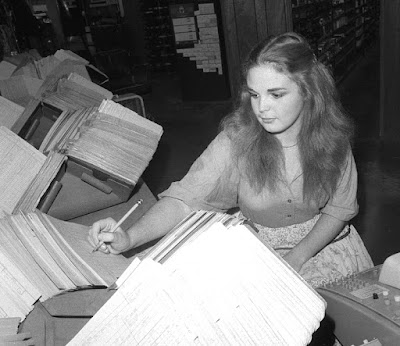

In the process of reviewing each negative, assessing physical condition and date, I’ve seen (and indexed) a great many unusual images. When newspapers were more local in their production and coverage, there was a strikingly personal touch to the content. Between the 1930s and early-1950s, I started to take note of a few sensitively composed images of people writing, even indicating the pencil-writers in my spreadsheet index. This cast of characters is at school, at work, at home, and outside. Here are a few of the gems (from the '30s - '80s, so far) with hopes that you’ll find some encouragement to write your days and journeys. Enjoy the photographs which are little worlds that now visit ours, and enjoy the continuum in which each of us participate.

gearing up

Below: Enthusiastic customers at Grant's Department Store.

at school

Below: Comparing notes.

at work

Below: Pencilling orders at the malt shop.

and for the Maine State Legislature (below).

wandering and musing

Above: Ideas are afoot on the grocery store stoop.

Below: Writer aperch in a cushioned jump-seat!

What's in your pencil box?

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

rock paper scissors

"A box without hinges, key, or lid,

Yet golden treasure inside is hid."

~ J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit

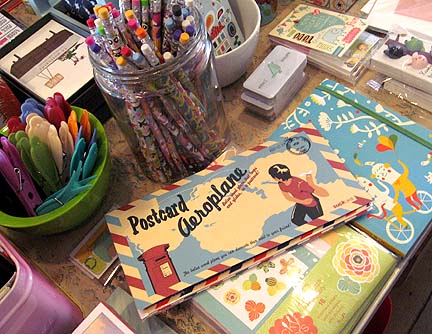

With the return of pleasant weather and more passable surfaces, the new season invites our travelling dreams. Road-trips may be of any duration- an afternoon or several weeks; ten miles or a thousand. For the moment, here is a place just an hour north of Portland, in the coastal town of Wiscasset, Maine- and a fine oasis loved by its customers: Rock Paper Scissors. The locally-owned stationer is now in its 10th year. Stopping in, as I like to do, for pencils and a friendly greeting, I asked the owner's permission to spotlight her shop on this blog. And we begin right here (below) on Wiscasset's Main Street:

Erika Soule (at left in the photo above) is the founder-owner of the shop. A Wiscasset native, her inspiration for opening the shop connects her commitment to making her livelihood in her hometown, her love of paper and art, and- as she says- being surrounded by things she loves. She began by selling bookbinding supplies, and housewares, and finally chose to focus on stationery and writing materials. "Buy what you love," she added, "and hopefully people will show up." Indeed, we do show up. The good word of an unusual, eclectic, and sophisticated inventory combined with the shop's neighborly atmosphere draws customers from hours away. Erika refers to regular customers who "make the pilgrimage." (In the above photo Erika, her customer, and I got into a conversation about typewriters- somehow- and that's my Olympia SF visiting the shop counter during one of my road trips!)

A view of the shop's arrays of journals, handmade papers, ephemera, and writing tools.

I asked Erika about the shop's most popular items. She began with pens such as Microns, LePens, "Aquarollers," by Itoya, and Pilot Varsity disposable fountain pens- all of which she demonstrated. Greeting cards are also very popular with all ages. In the photo above, Erika described the Apica "Twin Ring" journals which have become very popular, along with standby Rhodia and Moleskine blank books of varying sizes and paper styles. Quattro journals are another newly sought-after item.

Not to be missed, there is fuel for the graphite appetite. Erika's shop has long been my source for Craft Design Technology HBs. Pictured below are some amazing sculpted artifacts entirely made of graphite. These are unique items, each hand-carved.

In the photo below, Erika is writing with a graphite "branch." These tools do not smear or stain hands!

More popular items with customers are Japanese masking tapes (above) and journaling binders (below). The decorative tapes have more of the feel of a thick version of Magic Tape, and can be repositioned, and are entirely unlike what many of us know as painters' masking tape. Erika says these fly off the shelves!

Items such as these are enjoyed by all ages. The shop's customers include elementary-school-aged children, and span the generations.

As it may be evident by these pictures I took, people come to the shop looking for creative ideas. Being a longtime customer myself, I can attest to this serendipitous aspect of visiting Rock Paper Scissors. It seems there is always something new to try and people with whom to talk about the tools.

...and there's the shop's mascot and able assistant, Abby...

Along Route 1, just north of Bath, Maine, Rock Paper Scissors is at 68 Main Street (Route 1) in Wiscasset (the Prettiest Village in Maine), and their number is 207.882.9930.

(As yet, there is no web site.)

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

graphite roots

“seek, and ye shall find”

~ Matthew 7:7

Following a good few miles of walking I stopped to write a few words, aperch on a large rock. Looking from the panoramic ocean in front of me, and down to my notebook, the dark grey textured granite caught my attention. From the massive rock, I noticed the pencil I was writing with- and saw how their tones blended together as though from the same source. I wrote in my notebook, “I am writing with the earth of which I am formed.” We write and draw our lines and marks with the colors around, beneath, and above us. Formed from this earth, we write with earth upon this life's substrata.

Not long before that moment, I’d enjoyed a day’s adventure seeking out and exploring the ancient graphite mine site at Tantiusques, Massachusetts. Parts of the treads and seams of my hiking shoes still hold traces of the unusual orange soil from the terrain. I like the reminder. When I arrived at the location of several now forested-over deep trenches, I tried to imagine how the native Nipmuc prospectors would have even thought to excavate that particular spot and not another. Simply shuffling at the ground, my feet kicked up a clay-like ferrous soil. That may have been the tip to explore further. The Nipmuc used the greasy, sticky graphite to make ceremonial paints.

Graphite is a mineral, an allotrope of carbon (as is anthracite), and as any such material it must be mined. Forming in veins of metamorphic rock, combined with limestone deposits, graphite is identifiable by its black streaks. Its name is based on the Greek verb graphein, (“to write”) because of its use in the production of writing tools. A rarer type of graphite is its crystal form, among the world’s few non-metallic conductors of electricity.

Tantiusques, often pronounced “Tantasqua,” approximately translates as “the black deposits among the hills,” and is located in a remote area southwest of Sturbridge. The site was an ancient source of graphite long before is was shown to exploring Massachusetts colonists in the early 1630s. A few years ago, I read The Tale of Tantiusques, written by George H. Haynes in 1902. With captivated imagination, I determined to find the place. All I needed was agreeable weather and time to sojourn to an intriguing place that doesn’t appear on my way anywhere.

“The mine is situated in the midst of a tract of land,” wrote Haynes; “still, wild, and desolate.” Today, Tantiusques is protected by the Trustees of Reservations, and the area is near another protected area managed by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. In 1644, John Winthrop the younger, son of the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s first governor John Winthrop, purchased the mine and the area around it from the Nipmuc sachem. The agreement secured “ten miles round about the hills where the mine is thats called black lead.” Indeed, the Colonies were to supply England with the abundance of “all mynes and myneralls, aswell as royall mynes of gould and silver,” as we read in the records from the 17th century.

Winthrop’s goal was to raise as much as 30 tons of graphite from the mine, and he also hoped to find silver. As Haynes wrote, “The early colonists shared the hope that El Dorado might be discovered in New England.” Briefly put, the going was very rough. Tantiusques was located in remote inland wilderness, making transportation and maintaining a labor force difficult. Winthrop’s reports attest to how the high-quality ore lay deep in small veins, “it being very difficult to get out of ye rocks, which they are forced to break with fires.” Convinced his graphite was mingled with silver- both fetching high prices in London- Winthrop brashly wrote to his Swedish shipping agent in England, the raw material was “part silver, but this you must keep as a secret and not talke to any body about it further then it is to make pencills to marke downe the Sins of the People.” Later on, a London appraiser declared, “that which you call a silver ore is almost all iron.” The Winthrop family ownership and management of Tantiusques continued until 1784.

The post-Revolution and the War of 1812 evidently diverted energies from many ventures- including Tantiusques. By the time Frederick Tudor, of Boston, purchased the mine and its surrounding property just before 1830, Massachusetts became a center in the American pencil industry. Included in this region was the successful Thoreau manufacture in Concord, and graphite mines in Acton, Mass., and in contiguous southern New Hampshire. In the employ of Tudor was Capt. Joseph Dixon. At Tantiusques, Dixon and his son worked at the mine and founded the Dixon Crucible Company. Dixon was an entrepreneurial inventor who innovated a mirror-based camera viewfinder, a double-crank steam engine, methods for underwater tunneling, and a heat-resistant graphite crucible. He began his graphite enterprises, using Tantiusques graphite, in 1827, producing stove polish, foundry materials and lubricants, brake linings and bearings, non-corrosive paints, and woodcased graphite pencils. The Civil War era intensified the domestic demand for portable (and dry) writing material. Pencils became indispensible. By the early 1870s, Dixon Crucible was the world's leading graphite consumer and dealer. Pencil production reached 86,000 per day. Perhaps you are currently using Dixon pencils, which are descendants of the ancient Tantiusques mine!

By the time Sturbridge businessman Samuel L. Thompson purchased the Tantiusques property in 1889, Dixon Crucible had been well-established in Jersey City- close to the port of New York. After Francis L. Chapin’s purchase of the property in 1893, the Massachusetts Graphite Company was organized to continue developing the area, using more modern mining methods. As Haynes reported (in the present tense) in 1902, “Prospecting has been undertaken upon other parts of the property, and one short open cut has been made in which graphite of remarkable excellence was encountered.” These were Tantiusques’ last productive years, as all mining ceased by 1910. For the preservation of the site, the next significant year was 1962 when The Trustees of Reservations acquired the land with a gift from Roger Chaffee of Worcester Polytechnic Institute, a former student of George H. Haynes (author of The Tale of Tantiusques). Finally, in 1983, the Tantiusques site was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

When Tantiusques was in full production, most of the mining had been open-trench. One of the large trenches that is still visible had been dug 1,000 feet long by up to 50 feet deep, and only 6 feet wide. Once more, Haynes’ words from 1902: “The principal vein of graphite was inclined at an angle of 70 degrees. In following it an open cut was made some 500 feet in length, from twenty to fifty feet in height, about six feet wide. This deep cut has always been a source of danger; on the thirteenth of October, 1830, the fall of a great mass of the overhanging rock crushed to death two workmen and crippled for life a third.” Standing at the bottom of the vein today presents an oddly peaceful sight. It is a lengthy and angled trench, with steep chiseled rock and trees banked high at both sides.

Though I could find my way to the well-concealed and winding Leadmine Road, being a seasoned New England navigator, locating the Tantiusques site took a lot of persistence. Having missed at least three rounds of mild-weather seasons, and also having dedicated the time, I would not be daunted- and that meant taking all the wrong turns in good spirits. A very worthwhile adventure, rewarded as soon as I found a mine tunnel opening. From there, some very rocky trails ascended uphill revealing high-angle views of deeply-cut trenches. Considering the mine has been extinct for a century, my enduring impressions combine tranquility with the strange beauty of the place. Verdant natural growth covers pronouncedly human-carved terrain. Near the top of the longest trench I found, I could see the pond at the incline’s base which had been the landing-point of mining debris. Today, Leadmine Pond rests silently and glistens with reflected light.

The day, filled with chilled autumn sun, amounted to a moving and fascinating experience. In a new way to see territory I know well, it became clear to me that the tools I have been using are formed of the basis that supports living beings. Seeing the mine and walking throughout its environs brought some past experiences to mind, such as jobs I’ve had in dark and subterranean confines. And my visit, years ago, to pay respects to coal miners (dissimilar as the Tantiusques site is) was close to my thoughts when I crouched into the tunnel. Yet upward to the sky vault the trees. Pondering how all things have roots, I stopped to write about my lifelong search for roots of my own; I find shreds of them in scattered places. And thus, learning about who I am, my explorations are at once upon the surface and deep within. Two very small rocks from the inside of the mine tunnel are on my desk for me to be reminded of what transforms within. As memories are scribed upon the soul, my hands continue to write the graphical record. I know that I will think of Tantiusques when the winter snows cover the seashores near my home as well as the remote woods that have reclaimed an ancient graphite mine.

Eldorado found in New England!