“Adopt the pace of nature.

Her secret is patience.”

~ Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nature

With an extremely rare weekday off, I chose to stay in town and write outdoors. Not only that, I decided to write on the Eastern Promenade- a writing perch I’ve enjoyed for many years, long before having to move from my home in a suddenly-gentrified West End building. Indeed, last autumn- until it got too cold- I walked to the “Prom” as often as possible, getting away from the puny apartment, just to be able to look upward. Going outdoors to write allows me to transcend “addresses,” and their confinement. People travel to Portland from great distances, to be able to perch along Casco Bay. The scenery continues to be inspiring to me, just as it was for me last month in the Berkshires. Getting out gets me away from oppressive and bland spaces, as well as from the static recirculating air of the workplace. “Retreat” needn’t mean extensive travels; it’s really about stepping back and away from structure and demands. I could be from anywhere and come here to write, at the same time as being from here (which I am) and forget about annoying confines. The outdoors also provide an escape from alienation. Open, and accessible spaces strike a needed contrast from offices, phones, and lit screens- allowing me to listen to my thoughts and make some notes. Skies provide a taste of ceilinglessness (and how cooperative that my typewriter doesn’t redden or rewrite my made-up words).

Writing at the Eastern Prom, which includes a busy playground, brings to mind the day camps that were lights to my adolescent summers in New York City. Asphalt jungle childhoods comprise scarce amounts of trees and clean grassy spaces for playing and perching. There was always a lot of broken glass to sidestep, along with other detritus I stopped seeing after moving here to Maine to begin college. No doubt, the air was a comparison I could immediately make, and since then has always been rolled into what I’ve come to know as “the outdoors.” But humble as it was, day camp gave me a taste of things easily taken for granted in northern New England. In the city, the change of context brought kids like me on long yellow school buses out to the lush and landscaped parks of Queens- namely Forest Park, and for a number of years Kissena Park. Hardly any of the other kids were from my neighborhood: the blighted and dangerous projects in Corona; they were from just about everywhere else. But we were all together, frolicking outside, jumping through sprinklers, and fanatically playing baseball every single day. We were easy to please, once we had time and space. Perhaps some of us retain those traits. There was no structure and no technology- even for the camp counselors that watched over us, also serving as our umpires through all those raucous ball games.

From my high school years:

Above: Greenway Terrace, Forest Hills, New York City

Below: High School of Art & Design cafeteria, as we all wondered what was really in those sandwiches.

I’m one of those adults that can still think very much as I did when I was ten. The ache to have time and space to muse, around those fettered and adversarial school days, resembles the ache to have time and space to muse between job tasks and inane meetings. Free time becomes increasingly costly. For most of us, liberation is rare and at best incremental. Reflecting back, childhood redemption arrived in an unwitting combination when I was 13. My year began as I completed rigorous and intense religious studies, thus declared an adult at that rather young age. In my naive determination, I survived my final year in what happened to be New York City’s most overcrowded public school, which went by the heartwarming name of I.S. 61. Its schoolyard was surrounded by housing projects and scrapyards. The city was a good 2 decades away from gentrifying, and my daily walks to school were imperiled by gangs and packs of feral dogs. Almost all the threatening and thrashing ended for me with the post-middle-school summer at a healthy summer camp in the mountains of Upstate New York, followed by my parents’ purchase of a house in a strikingly beautiful and safe neighborhood- still right in the city. And finally, still at age 13, I began my sojourn of secondary education at the High School of Art and Design, on the tony east side of Midtown Manhattan. A whole lot in a short year. My father gave me my first bicycle, enabling me to run a lot of errands, including grocery shopping. I explored all the streets of Forest Hills and contiguous neighborhoods, also toting my first camera- which had been a 13th birthday gift.

My Rudge-Whitworth bicycle, which I purchased used for $20 to replace the new bicycle robbed from me by muggers.

Above: Photo I took in 1981, in New York City.

Below: Photo I took (I still have the Rudge) recently at Acadia National Park, Maine.

The bicycle symbolized freedom and an enduring sense of self-propulsion. I would joke about drinking a glass of milk, then bicycling the length of Queens Boulevard and over the 59th Street Bridge en route to a library I frequented on East 38th Street. All on one glass of milk, as I’d say. One afternoon, while bicycling with a neighbor through Flushing Meadow Park, I was accosted and mugged at knifepoint, forced off my shining new bicycle. I still remember this well, and can recall the sheer powerlessness of that event. At my summer job in a supermarket, I saved my earnings to buy another bicycle- a used one that I defiantly considered to be too ugly to draw any thug’s attention. I still have it today, driving it throughout the Portland area, including all the carriage roads in Acadia National Park. Self-sufficiency continues to be its own brand of liberation. Alas, and as I’ve learned, childish and childlike are really two different traits. At best, that early spirit endures by adaptation. As well, self-sufficiency shows its hard limits, particularly in the powerlessness of housing searches, employment scavenging, and economics. Recalling Saint Augustine, “I do not know what I do not know,” and thus I want to know what I don’t know. If there’s any way to improve things, it must begin with avoiding prior mistakes.

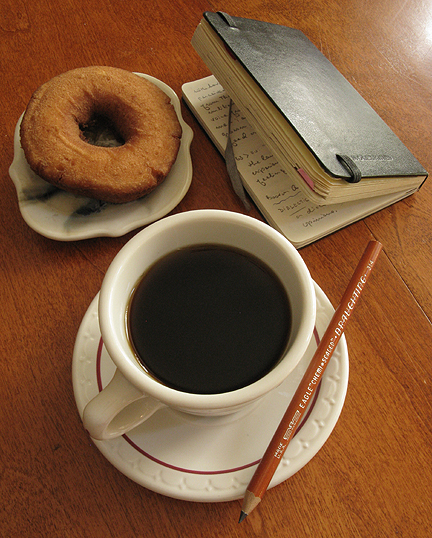

How much of a factor are our interpretations that are based upon our subjective perceptions? Obviously, something entirely subjective is my taste for perching outside to write and read in 40-degree temperatures, which I find perfectly comfortable. Then there’s the fascinating aspect of how syntax plays a role in how we view and depict our discoveries. For example, traveling to a location with a variety of cameras allows me to photograph similar motifs with different formats. The images will look distinct from one another, based upon the tools I’m using. Same with writing: pencils, pens of varied construct, typewriters, and computers will each lead to results reflecting the tools’ influences. Within this is the example of journaling with a dip pen, requiring many regular pauses to re-ink the pen, while the mind continues its train of thought. Those pauses surely reflect what is written. I’ll often switch writing instruments, when I notice aridity in my words. Varying the vantage point is also as effective with writing as it is in photography. Getting outside amidst the swirl of nature permits for an appreciation of Emerson’s description about the patient paces of nature. Light, skies, and horizons will surely affect how I interpret what I see, and how I interpret my thoughts. In a similar sense, I write during my mid-day breaks inside the Archives stacks, as well as aboard lurching city buses. What I notice and the ensuing words are affected by their situations of notation.

When I’m not on the job, and I turn away from doomscrolling online searches for apartments and employment, while the blaring and trampling from upstairs disturbs the peace, I know to go outside. Beneath the skies, there are no upstairs. Life gets to return to looking open-ended as it did when my friends and I would lie on our backs in green and sunny Kissena Park, just talking and looking up at airplanes going to and from LaGuardia. The paces of nature are surely not those of such humans as those among us who use the expression, hurry-up-and-wait. Coaxing the inertia out of the wheels of progress is exhausting. During the thick of childhood, time slogged like a schoolday. It felt endless. In retrospect, that was a brief period of time- its space on my timeline diminishes as the adventure continues. Looking back exclaims the necessity of looking ahead. My decades of tireless efforts have yet to pave ways to my profoundest wishes, to exercising and really seeing my best abilities coming to fruition. How close is success? Is it completely out of reach? I’m daring to believe it isn’t, notwithstanding my scarce resources and lack of influence or allies. Echoing Saint Anselm’s prayer in the Proslogion, “I have still to do that for which I was made.” Yet, the stuff of eternity does not include accolades or material. The moment and all subsequent time stands for me to redeem. Knowing how to redeem liminal time is a daily and constant challenge. Having little more than faith and gumption, I’m left to heeldigging trust, insisting upon finding the sacred in the ordinary. Such thin rations need the light and rain of the outdoors, for the vines of latent presence to proliferate and provide.