“One who wishes to advance toward wholeness

should, by meditation, awaken, sharpen, and direct the

sting of conscience; hold out, broaden, and turn back

the beam of intelligence; concentrate, feed and raise

aloft the little flame of wisdom.”

~ Saint Bonaventure, Love Enkindled

Tuesday, June 10, 2025

enkindle

Thursday, April 24, 2025

ideals and possibilities

“By judging the truth of things according to the divine measure,

we acquire wisdom; by embracing the supreme good,

we are liberated to enjoy and use the goods of creation

for the enrichment of human life.”

~ Zachary Hayes, O.F.M., The Hidden Center.

The lead quotation for this essay comes from a book written by a modern-day Franciscan, addressing Saint Bonaventure- a fellow Franciscan who lived in the 13th century. The consistency of insight to this reader is such that I have the impression of studying a philosophical writer reflecting upon his own esteemed ancestor. I read the sentence to my philosophy students, as an example of idealism- and good, lofty one, too: Acquire wisdom and improve the lives of others. Cultivate what is needed to practice the golden rule. We subsequently had a lively Socratic forum about such divisions of idealism as the subjective, the divine, the ontological, and the epistemological. These topics will be revisited in greater depth, seeing how strongly they’ve resonated with the group.

One of my colleagues added encouragement, having participated in my treatment about how happiness ("eudaemonia") is defined in philosophy, generating an enthusiastic discussion. “Keep doing these,” she added, “we all need this.” Admittedly, so do I. Perhaps the study of philosophy- or philosophizing, in itself- may be just a bit escapist? Well, that’s worth another group forum. For the moment, I’ll say it’s a combination of reckoning with the surrounding world, and consolation. All points lead to understanding, to making sense of perceptions. Beyond the abstraction of thought is the praxis of a physical sign. The illuminative and the literal riding in tandem, searching for signs. Spring began showing itself at least a month later than usual, in northern New England, with persistent cold temperatures clashing against lengthened daylight. Eager for new growth, both metaphorically and three-dimensionally, I have my camera close at hand to photograph what treasured signs can be found and savoured. Living to such ideals as Bonaventure’s, and the later Bergson’s “realization of what is yet to exist which will provide greater significance” relates well to the new promise of spring.

For a week of respite, my first in four months, I recently enjoyed a nourishing string of days in Boston. My studies at the Athenaeum were centered around encouragement and assurance, all penned by various theological thinkers. More philosophy for inspiration. I select the readings through bibliographies and lengthy catalogue searches, followed by submitting the requests several weeks before my arrival. Those e-mailed communications signify initial forward motions toward pilgrimage, choosing my direction immediately after having my time-off request delicately approved. As the swirls of preparation, packing, transportation, and logistics settled, the brilliance of great company and thoughtful studies emerged. A lingering thought occupying many musings was a suggestion to consider the possible as an antidote in the struggle against confining and incessant frustrations. What possibilities are available while swamped in recessed economics, undercapacity, and treadmill existence? Turning toward an ideal of possibilities brings me to the captivating word, potential. Convinced for many years of the underutilized potential for my skills and experience, my perseverance toward better days continues to be fueled by the prospect of future opportunities. Necessary components and energies are at the ready; but there needs to be a convinced and welcoming receiving end. Realized potential as an ideal is the stuff of daily and constant prayers, immersed in quotidian productivity and conscientious service. The magnitude and immediacy of responsibility eliminates the option of waiting around for the miraculous. But a state of readiness can still abide, seeking out the possible, despite the encroachment of negative limits.

While drafting this essay, and during my recent week of commuting, my reading included two new books by Pope Francis, one which included these words...

“Do not surrender to the night; remember that the first enemy to conquer is not outside: it is within you. Therefore, do not give space to bitter, obscure thoughts... Faith and hope go forward together.”

(Light in the Night, 2024)

...and the day after reading these sentences, I learned of his passing. Pope Francis wrote in gentle and direct tones, as a seasoned mentor. The surrender he wrote about refers to something familiar to me, and I absorb his exhortation as a warning against my habitual tendency toward immersing thoughts with impossibilities. Entirely unusual for his position, Pope Francis engaged with this world and its many humanitarian crises, sharply critical of injustice- yet his idealism remained solidly intact. As with Brother Roger of Taizé (whom I knew), living to a similar age, Pope Francis consistently wrote about hope. Both leaders approached the entirety of life as a pilgrimage of trust. Brother John, former prior of Weston Priory (whom I also knew), passed away last month at the age of 100. When an esteemed leader- especially an elder- passes from our lives, and we notice traits and turns-of-phrase attributable to them, we begin to realize a spiritual inheritance.

“In revealing the possibility of a life lived in the presence of God,” continued Zachary Hayes’ gloss of Saint Bonaventure, “it reveals what is in fact the original possibility of humanity, created from the beginning in the image of God.” We’re reminded that various possibilities are in our midst to be discovered, if the “big picture” isn’t lost, while struggling to create wider opportunities. During my recent studies at the Boston Athenaeum, I read the inspiring Life of God in the Soul of Man, written by Scotland’s Henry Scougal in 1677. His term for spirituality was the divine life, and his intention for the work was that his readers derive encouragement to stay the course through the challenges of hardship. His enjoinder to continue making progress in faith has the reminder that with wholehearted devotion, “we shall have all the saints on earth and all the angels in heaven” interceding for us. Readers are instructed to take heart, keep faith, and not be afraid. “Away with perplexing fears,” Scougal insisted, continuing with:

“We cannot excuse ourselves by the pretense of impossibility.”

... which is to say that we mustn’t be so quick to unquestioningly say “it can’t be done.” Indeed, we have yet more idealism, and I welcome strengthening words, relieved to discover such fine company. Studying written treasures is more than reason enough to travel. As I witness the passing of various visionary leaders that taught generations preceding and including mine, I’ve become increasingly aware of thinning ranks, in no less than these darkened times. Let us all consider our reception of torches passed into our hands, no matter our states of readiness. Many are already teaching others, unwittingly and by profession. There is little choice but to carry on. Now, how shall we find and flex our discovered possibilities?

Monday, January 1, 2024

looking forward

"The kingdom of heaven only costs as much as you have."

~ Saint Gregory

Between the completion of various projects, commitments, and the subsequent holiday weekends, I was able to take a few days away for a quiet retreat in December. Respite time has been extremely rare in the past four years, now generally known as the “covid era” (albeit with the first year being under quarantining orders). Laborers on pared-down staffs often became the surviving hands-on-deck in their respective places of work. I wrote about being among “the working wounded;” yet truly thankfully employed and bill-paying, but holding course while staving off the burnout in my midst. This pandemic era may be tailing off now, but economic and societal conditions have been permanently altered. Suffice it to say, many practical matters are simply too dissimilar to those of four years ago to be as reliable as they were. Try finding an actual hardcopy newspaper now (and when you do, notice how the price is exponentially higher). Notice how social interaction is much more electronic than in-person, how commerce is relegated to impersonal self-checkout, and how a “wallet” is now stored financial data. A “menu option” left the context of restaurant dining, and became a term of robotic telecommunication. As recently as four years ago, taking earned time off meant physically turning to a colleague and comparing calendars; it has since become cajoling and electronic wrangling. Much more than the rigors of earning the time, there are added equations in being able to use the time. The bar having been raised, it is necessary to jump higher with the changed rules of the game. Of course I can do this, and I must.

As the will makes for the way, I recently managed to negotiate for a very modest amount of respite and backup coverage. Eight months in the waiting, the worthwhile carrot at the end of the proverbial stick was a stretch of days for slivers of spiritual health, silence, and writing. Having very little time to plan, as well as to find coverage, I searched for a place that would make space for a pilgrim during this time of the year. An Advent intermission from the beaten track and the routines was what I needed, and a very kind invitation came from a Cistercian community in Massachusetts. Getting through the subsequent complexities related to springing forth for a short time, the more pleasant parts of preparation ensued.

As I’ve known for years, most any sojourn can be a pilgrimage; it needn’t involve great distance. Intention is basically all that is needed. For a pilgrim of trust, the purpose is to sanctify time and place for immersion in the sacred. In anticipation, I began to assemble trip necessities such as writing and reading material, clothing, camera, and some groceries to add to the guesthouse provisions. This was my first time both at Mount Saint Mary’s Abbey, and in southwestern Norfolk County, though I know the general region. My drive to Wrentham took about three hours on roads that traverse familiar New England terrain that comprises cities with repurposed mill buildings, farms, forests, and villages. The winding country road leading to the abbey slices through tall pines, and must be navigated slowly. Arriving to gentle greetings, I proceeded to the guesthouse and found an envelope on a lit end-table which welcomed me in cursive flourishes resembling the tones I’d heard moments before. Setting my satchel and duffel bag in my dormered room, I immediately and gratefully felt the quiet of the place, along with like the country air. Two of the community’s guest sisters and I spoke about the vitality of contemplative silence. We talked about how burnout endangers the souls of this culture’s understaffed overworked. We also made reference to weather alerts pertaining to an approaching storm. From there, we all prepared for vespers. Above all, being in late-December I was among kindred spirits in anticipation of the Advent.

Gradually settling into the old, familiar monastic rhythm, I immediately noticed how tightly-wound I’d been for too long. Equally old and familiar is the sense of reverse-inertia: slowing down to a halt needs quite a long runway. The soothing tones of sung liturgies harmonize with the natural landscape, helping to transit from stressful vigilance to receptivity. Even as the rainstorm arrived, the patter on the abbey church roof pronouncedly audible, the peaceful ambience of the place simply absorbed all sounds. During an evening service, the rain intensified into a backdrop for the readings, chanted psalms, and silent adoration. I later heard the continuum of pelting rain on the skylight immediately overhead in my little room.

The storm amounted to something similar to a hurricane, with torrential rain and 90mph winds persisting throughout the following day. I cannot remember ever seeing such hard rain. Looking from the guesthouse windows reminded me of driving through a carwash, but this went on for more than a day, eventually causing felled trees and a regional power outage. Along with the loss of electricity was the loss of heat, hot water, and backup generators. The abbey had to cancel services. We used plenty of candles in the guesthouse, dining on leftovers, still savouring the spirit of the community. Even considering the cold, dark night ahead, I did not try to make an early trip back to Maine; the storm was moving north, and I would’ve been contending with hazardous conditions all the way up. The best thing to do was to patiently wait out the weather. Inevitably the storm passed, yet the outage was predicted to last another day. Washing with cold water the following morning, and downing day-old tepid coffee from my thermos, I packed my car for the return in daylight. Before taking to the roads, I made sure to thank my hosts and to bask in the healthful silence of the unlit abbey church. While the retreat had to be shortened, there was plenty to cherish, such as an open-ended welcome to come back, some new friends, and the acquaintance with an oasis new to me. Driving between large branches and fallen trees, en route to highways and hot coffee, was that among other things I have hope itself.

“Still will we trust, though earth seem dark and dreary,” William Burleigh composed more than a century ago; “Though rough and steep our pathway, worn and weary.” Indeed, I returned from a shortened sojourn, back to work and the search for better, holding fast to Advent light as night falls in the afternoons. A new year approaches. Perhaps a suitable excuse, as the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve may not automatically regenerate much more than a calendar. As the Battle for the Better continues, albeit via Advancement by Small Measures, I’m looking to the upcoming year with the usual ache for a good future. Fully aware of being in the thick of significant work, there’s every good reason to keep at it. Looking forward is the best thing I can possibly do. I needed at least a year and a half to write the housing-loss grief out of myself. Now it’s the forward gaze that indicates preparation for the granting of my most vigorous wishes. It isn’t really difficult to insist upon looking forward, with essentially so little left for which to look back. If anything at all, I’m looking forward to returning to the abbey in Wrentham during better weather. Grand things manifest because of humble things. While commenting about Psalms 13 and 14, Saint Augustine remarked that “Interior and unceasing prayer is the desire of the heart.” Essentially, one’s profoundest hopes are distilled into intentions of the spirit. He added, “The desire of your heart is itself your prayer.”

Reminiscent of my original profession and my most fluent language: photography, I find my reminders for the present. Practitioners of the craft like me can recall or point to studios, portfolios (effectively our resumés), projects, exhibitions, and tools of the trade. Far and away, the most important aspect is a cultivated sense of vision. This transcendent ingredient is also known as “the photographer’s eye.” Artistic vision, as I’ve found, can be applied to numerous types of work and facets of life- even the human imagination. As a working archivist and conservator for nearly 26 years, I’ve often envisioned completed results (and their remedies) ahead of time. But that doesn’t mean I can predict the events of the new year, as these involve much greater complexities than those of my sole efforts. Once again, and at the very least, I can put up my end of things, and I know enough to "forget those things which are behind, and reach forward to those things which are ahead, pressing toward the goal for the prize of the upward call*". Everything is in need of improvement; bring on the new year.

_____

*Philippians, chapter 3

Thursday, October 26, 2023

standpoint

“In the words of the psalm,

‘For with You is the fountain of life;

it is only in Your light that we see light.’

Human beings have no other secure standpoint

for being certain about anything at all.”

~ Douglas Dales, referencing Psalm 36 and Saint Bonaventure,

in Truth and Reality : The Wisdom of Saint Bonaventure.

My ongoing philosophical studies have continued to serve as healthful oases amidst chaos and setbacks. Such pursuits into contemplation also produce learning and constructive thoughts for me, as well as teaching material which I gladly share. With material needs as vital as housing and work in protracted fluidity, survival requires waystations in welcoming forms. As the Word is a lamp to my steps, so it is that in Divine light that I can discern light. Aspirations live in ethereal mists, and thus hopes are not always solid enough for my mortal self. A comfortable place to live and a really good job would do wonders to the morale, with all searches continuing as fibers in the general cord of the pursuit for improvement. This is not to say there aren’t present-moments to savour, because there are- both modest and grand. I’ve surely learned to constructively make do, under pared-down circumstances, throughout my working life. Yet I’ve never stopped hoping large and working ambitiously. It’s equal parts survival, fulfillment, and acknowledgment of the great teachers and mentors I’ve had.

Because my studies are self-directed, I’ll stay with a topic until I’ve covered enough ground to my satisfaction. This practice dates back to my beginnings with philosophy-teaching, in 2015, and intensified during the austerity of pandemic-era quarantining. Lifelines of learning and writing still stand as reliable constants and sources of mental strength. I chose to revisit Saint Bonaventure’s Itinerarium, which I had first studied as the severities of early 2020 set in. Now, following deep dives into the works and lives of Wyclif, Erasmus, Colet, and the Devotio Moderna, the 13th century Bonaventure appears to me as a proto-Renaissance thinker. He was also a university professor and a Franciscan, blending charism and pedagogy with “No one comes to wisdom except through grace... One does not come to contemplation except through perspicacious meditation, holy comportment, and devout prayer.” Bonaventure has some aspects of the scholasticism in his midst, balanced by his mysticism, with metaphysical statements such as, “We are led to re-enter ourselves, that is our mind... one cannot enter within, unless by means of Christ, who says I am the door... but we do not approach this door unless we believe...” Navigating thus far- from Bonaventure’s Itinerary, to some of his commentaries, to the Collations on the Hexaëmeron I continue finding more to nourish me, and will simply keep on reading. It’s as though I’m standing near The Seraphic Doctor himself, with reverent devotion.

Beginning in the middle of last year, I’ve had to function without a comforting home base- or as Dales observed (and quoted above), “a secure standpoint.” Between both work and housing instabilities, the vantage point is at once being between two dead-ends while also admitting that everything is up in the air. Thoughts of this reality at night are threatening. Thoughts of this at noon the next day almost seem exciting. But all thinking and activity take place amidst the din of instability and uncertainty; as much above it, as under it. Missing a physical, welcoming “home base,” that proverbial secure standpoint takes shape as a state of being during which I sense assurance. While frustratingly searching for a comfortable perch, I’ve thus far noticed ephemeral slivers of rest during times of study and writing: reading at bus stops, or sometimes late at night in the crunched hovel after the loud neighbors shut down, and writing during my thirty-minute lunch breaks, or outdoors any chance I get. Not terrible, making room for gratitude, but always too brief and just under the tension radar.

For many years, I’ve called momentary intermissions tagging up which is a baseball expression describing a baserunner’s safely advancing amidst a play. During my 14 years of fulltime work in the pressured commercial photography field, I’d start days and find breathers “tagging up” at the counter of my studio darkroom. It was my base of operations, with two slick, imported Durst enlargers bolted to the surface, and filled with the tools of the custom photographic trade. To help me feel at ease during sickeningly stressful times, I decorated the place and had a small stereo system. Just about everyone I knew in the profession listened to music to keep up the pace of production; for me, it was new wave and opera. And I always had a thermos of coffee with me, as I do now. My memories of closing the darkroom door and gathering my wits for the next project come back to me when I do something similar- albeit in much shorter snippets, resetting during breaks in the archives. The building that housed my studio was torn down in 2016. Indeed, I photographed the demolition.

With the business and all the people who passed through the place as workers (many of whom I photographed), customers, friends, and vendors gone, I saw the large piles of debris frontloaded away in dump trucks. Six years later, I lost my home of nearly four decades, the building being converted into elite condos. These are now simply locations, their respective histories and lives syphoned out. They are past and gone, but here I am now and straining to look forward. Places such as cities or neighborhoods or buildings, I’ve learned, are stages. It’s about souls, more than about streets. Solid places to regroup thoughts and broaden perspectives are essentially replaced by points of reflection. My writing and reading are always with me, providing ready clefts of stability- lulls in the battle. Journaling affords the ability to write through trials and get them out of my system. Movements of conscience take time. In my journals, the term point de repère- which actually means a reference-point or a landmark- parallels how I’ve come to see moments as respite. And such metaphorical landmarks can be anywhere.

A better side of remembrance is to recollect what we’ve learned. An individual as vast and inspired as the Apostle Paul wrote of his occasional rearward glances coinciding with reminders to himself of graces along his arduous path. I call this stocktaking. What’s good? Even between two dead ends, a burgeoning life reaches heavenward. Managing to schedule my first weekday off in three months, I made it a reflective day. “What’s good” included appreciating the outdoors at midday, chatting with friends, putting something away in my savings account, getting a very long-overdue haircut. Simple and understated, yet somehow luxurious. Profoundly missing those twice-yearly retreats I’d make- before 2020- something I can do is to find bits of time on weekends to recollect and accentuate graces learned. Among numerous turns-of-phrases I’ve learned from the monks of Taizé (and I’ve written down many, as well as words from the monks of Weston Priory), is the expression almost nothing. In context, this is to say there is always something one can do, “even with very limited means, with almost nothing,” to progress on the voyage to sanctification, and to help others. “See what you can accomplish with almost nothing,” Brother Emile once said to me. I use this at work, always aware of the spiritual/material ambiguity. "With almost nothing, with very little,” Brother Roger taught, “we can live something beyond all our hopes, something that will never come to an end." A beautifully hopeful thought.

Another savoured expression I learned in Taizé is to “live in the dynamic of the provisional.” Consistent with the positive practicality of seeing what one can do with a lively spirit and almost nothing. Consider the fluidity of the present as the provisional challenges individuals to exercise the dynamism inherent amidst our temporal situations- which can be improved as we find ways to improve our perspectives and abilities. Perhaps our most enduring landmarks are within, away from heavy demolition vehicles and exploitive developers. When our points of reference tend from the physical to the spiritual, their properties do have a dynamic in our provisional reality. Hardly the seclusion of a studio, or the coziness of a Victorian livingroom, I await the daily workbound bus in the East End while looking to the skies. It rains a lot here, and I deal with the uncanopied bus stops by wrapping my books in plastic and using a lined water-resistant satchel. Looking up, I’ve taken to musing about how landmarks live in our spirits. If they’re real and important enough, I’ll write about them. The cutting-edge is whether to be constructive or to eat my heart out; that’s quite a choice. “I know both how to be abased, and I know how to abound,” Paul observed as he addressed the Philippians. This comes to mind as I’ve watched many colleagues over the years burn out, while I try sensing the boundaries and do all I can to avoid becoming damaged goods. Keeping in good energies is essential in the reach for better days. “Pray without ceasing, and in all things give thanks,” wrote Paul to the Thessalonians. What supports our hopes? Causes can find me unwittingly, even at weatherbeaten bus stops, wielding my umbrella and a book with this grounding paragraph by Francisco Fernandez-Carvajal:

“We mustn’t forget that our greatest happiness and our most authentic good are not always those which we dream of and long for. It is difficult for us to see things in their true perspective: we can only take in a very small part of complete reality. We only see a tiny piece of reality that is here, in front of us. We are inclined to feel that earthly existence is the only real one and often consider our time on earth to be the period in which all our longings for perfect happiness ought to be fulfilled.”

Commenting about the determination of the humbled Zacchaeus (Luke 19), Bonaventure wrote, “it is the nature of genuine eagerness, which draws the soul to Christ, that even if obstacles are thrown in the way, its desire is not broken, but is the more enkindled.” Referring to my current studies as the Bonaventure Adventure, complete with a monthly day at the Boston Athenaeum library for replenishment, I’ve also made various side studies of his fellow Franciscans Saint Anthony and Saint Francis of Assisi. Comparing notes with a correspondent, I now know of the Franciscan Fr. Dolindo Ruotolo, whose extraordinary life gave the world a very simple devotional practice of openness to completely trusting the Holy Spirit within, called the Surrender Novena. The latter word means nine, as in nine consecutive days of focused meditation upon surrendering one’s will to God’s will. For example, in day eight’s reading, Ruotolo wrote in reflection of the Divine voice, “Repose in me, believing in my goodness, and I promise you by my love that if you say, You take care of it, I will take care of it all; I will console you, liberate you, and guide you.” I’ve been journeying through the past month with this compelling discipline. An elder friend of mine says it best: “Surrendering is so inviting; It sounds so easy until you try. Almost immediately after surrendering, you take up the problem and start dragging it around with you.” I couldn’t have expressed it better.

Surrendering one’s personal will and mortal navigational abilities to the very force of Creation is a formidable discipline that requires its own vigilance. In the throes of intense searching and applying, there must be surrender of all the subsequent worries. And there are many. What will happen? Why can’t this or that be so? What wrongs must I correct? To add to my counterbalance exemplified in Ruotolo’s prayer are those of Brother Roger in his essay, From Doubt to Humble Trusting:“Let your anxiety be transformed into the trust of faith.” And there are thick, embedded layers of anxiety. Consciously implementing this spiritual practice is the adjustment of a way of thinking and being, trying to surrender my attempts to control what is out of my influence, and not to fret. That is a major challenge. I can just hold up my end of things, searching and presenting as well as my experiences inform, always looking to improve my pitch. A devotional practice emphasizing humility and surrender causes- even forces- me to entrust my efforts to God. All at once, struggles expose limits, and defeats ignite more rallying to transcend. To cease is to fall backwards. Yet here again, surrender exhorts that I release all the worries that tend to follow my best attempts. Submit those carefully-phrased credentials at uploaded attachments, and then detach. The same trusting confidence in attaching files must go with detaching from the appealing ads. The prayers of surrender are about confiding, entrusting, and releasing fears and worries. Plenty still for me to learn, as I attentively correct my missteps and continue seeking a secure standpoint.

Thursday, December 30, 2021

newness

“Even so, we also should walk in newness of life.”

~ Romans 6:4

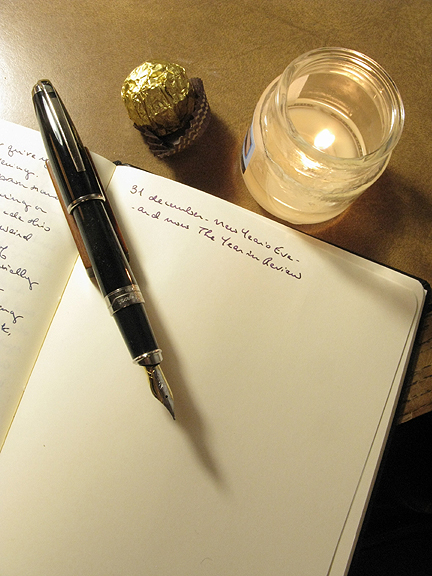

My voyage with journaling began in July 1994. Later on, graduate school caused my written entries to be regrettably intermittent. After 2000 I came to depend upon daily documentation and reflection, and the practice continues to this day. Throughout my years of writing, I’ve used the days leading up to New Year’s Eve to create retrospective “year in review” summaries. At first, I made the lengthy journal entries into Time Magazine- style features, as in “the year that was.” After a few years, these summaries became something I fashioned into several days of shorter journal entries, giving equal treatment both to events and to impressions. Without writing, telling the months and years apart would be even more difficult and surely blurred. The covid era surely represents this. It’s a snowball of largely dissimilar months, whose grip set in by the Ides of March 2020. Since then, living has been amidst minefields and restrictions. Thinking back to the world before that date, I remind myself that “everything was at least two years ago.” In keeping with my own custom, I’ve begun gathering my handwritten thoughts to recap the year which- if anything- feels as though it’s in Month 23. It is indeed a looking back, but always attempts at forward motion- traction or not.

The contrast is appropriate, connecting the establishing of winter and long nights with a season traditionally marked by newness. The Christmas holiday season has also long been relentlessly exploited commercially, with advertising beginning many weeks before Advent. Pandemic life has muted some of the competitive spending drives, forcing diminished budgets and smaller gatherings- if any. Yet the week between the western/Gregorian calendar Christmas and New Year’s Day continues to be a liminal span for various forms of reflection. The plague rages on. Will the coming year be an improvement over the one just past? How to look forward with anticipatory hope, in the bleak midwinter?

My self-determined directive is to continue seeking light in the darkness of these times, while trying to tangibly exemplify that light. For nearly two years, it has been impossible to travel or to even buy some weekdays off to rejuvenate. My semiannual pilgrimage retreats of many, many years have had to be compressed into a few occasional hours during a weekend so that I can continue being gainfully employed. Pushing back for the cause of spiritual health has also stretched nights into times of carved-out silence and study. Not doing this actually worsens the exhaustion. Admittedly, this is a trial that must be endured.

Newness begins with a thirst for promise, even for the haggard and worn. One recent midnight while preparing for the subsequent reveille that would return me to the same darkness, I methodically set up my coffeemaker and what I’d need to make next day’s entry as effortless as possible. Thinking of the combination of obligations and wishes while tidying my writing table, I remembered how an old friend used to call himself “a kid on Christmas morning,” and how that attitude helped him stay inspired. I wouldn’t describe myself as such, but there was something I liked about that sentiment. A soul’s renewal is as much a mystery as is the desire for newness. Do we inherently sense the hope of renewal? It is a fascinating thought how we seem to naturally find our own renewal- or at least the will to seek out our rejuvenation. Is this somehow built into our nature? I think we reflexively salvage the pieces we can find of our existence. The recent devastating natural disasters remind us of this. Victims who escape with their lives are looking for remnants from their households, their histories, and where their continua left off- at the times when their worlds were interrupted so they can recommence. In the less-cataclysmic scenarios, there somehow exists a natural drive to pick up and continue on. I believe this to be more than survival instinct, but the reinforcement of the holy spirit of new life. While more than enough reasons can be enumerated to give up hope, wondering about what is actually improving in our midst, we still tend to resume our searches for better and more meaningful lives.

During this year’s holiday season, I’ve noticed myself bristling more than usual at overused Christmas songs. They brought neither comfort nor joy, even to this believer. I fled to the consolations of Telemann, Bach, and how the occasion is quietly known as the feast of the incarnation. Yes, indeed, there is the commemoration of the Nativity. Not to be lost is the parallel aspect and infusion of the Divine within all whose lives return the embrace. Incarnation manifests to an ordinary human as transformation, and the latter builds an inner strength to be grateful while bearing up against hardship. Enduring the plagues in late 14th century Holland, Gerard Groote wrote, “May it never be that tribulation produce in us a faint heart; a faint heart, confusion; and confusion, the desperation that destroys.” Ancient texts accompanying this season include the name Immanuel, which in Hebrew means God is with us. Over the years, I’ve come to reverently refer to the So Near. As I’ve learned from the monks of Weston Priory whose doxology is to the Creator, Word, and Spirit of New Life, I understand the value of finding meaning beyond overused expressions.

The current provisional journey is embedded within an incalculable pilgrimage. Trying to take stock of the good that is, of the silent graces too easily overlooked, I try to be attuned to available inspiration. What is within my reach? What don’t I know that I need to know? Are we to search for newness, or enable renewal to find us? I wonder to what extent the spirit of rekindling is based upon unseen certitudes of which we could be innately aware. Perhaps there is a balance of proportion between a person’s determination, and a providence over which there is no control. And within that sense of resoluteness, does it begin with one’s desire to give rise to renewal, or are we brought to think about it from beyond ourselves? Do I procure the lamp and illuminate it, or is the already burning light catching my attention first? Unsure of what to make of the broader ailing world, as well as my own daunting setbacks, my thoughts turn to how all of this is about endurance. The transitory present is an impermanent trial. Distances and times between now and turns in my fortunes are impossible to tell. Opportunities remain out of reach, but hope remains available. Hopefulness increases the will to endure. When St. Paul wrote about how “hope maketh not ashamed,” he wanted his readers to confidently animate conscientious faith. Newness must ever be kept in mind. And kept in mind and practice with unwavering insistence.

Friday, December 17, 2021

perilous journeys

“Trusting faith is called a crystal well

because the waters of spiritual goodness flow

from it to the soul, although it is night.”

~ San Juan de la Cruz, The Spritual Canticle

advent wilderness

Generally speaking, we embark upon an adventure with expectations of resolve. We’ll invest in the engagement of a challenge, intending success. For the most part, one takes on a project with the idea of completion in mind. Beginnings are hopes exemplified. Our cultural experiences are replete with stories, novels, and films that travel an arc from launch through hardship and on to cathartic conclusion. Many dramatic biographies work as such. When I take on projects and pursuits, every provision and effort point toward thorough and sturdy completion. Some enterprises require more time than others; duration cannot always be ascertained at the start. But the important thing is to make progress, move in a forward direction, and maintain faith in the vision of fulfillment. Occasionally, courses of action need to be adjusted, informed by instinct and memory. I’ve often heard myself say within, “no- don’t do that again,” or “a version of this has worked well before.” I’ll work out dilemmas in my journal, like puzzles, allowing the written words to reflect back at me for some analysis.

But what happens when the craft is blown off course and both direction and destination become uncertain? Has forward motion been reduced to the plain progression of time? Do there remain chances to safely stop and recalibrate? How critical is the element of time? During this Advent season, amidst the second calendar round of the covid era, the end of the pandemic is out of view. The annual December weeks, commemorating movement through darkness toward light and nativity, historically direct observers to promise and assurance- and this continuum has persevered through millenia of plagues and wars. Upon my own trail of healthful contemplation, following the texts of the divine hours, these times bring me to notice a precariousness revolving around the signs of presence. The ancient readings describe the Advent voyage as being through a desert, even a howling wilderness. One very early pitch-black morning, with breviary and coffee, I noticed the prayer, “Watch over our welfare on this perilous journey, and keep our lives free of evil until the end.” The words “perilous journey” stayed with me throughout the day. Being a seasonal reading, I know I’ve read this before- but I notice it now.

Navigating through a sleet-spattered windshield yesterday, the phrase returned to me, recognizing the indefinite present as a protracted series of perilous journeys. The way forward is my best rendition of forward motion. Logistics have prevented me from taking respite time for two years and counting, confining reflection to the watches of night and an occasional weekend day. But I am holding course to the best of my abilities and resources. As usual for me, though appreciating the context of Advent season, I continue to be ceaselessly fascinated by the mysterious Magi. The written record leads to the Nativity, but the westward-voyaging astronomers disappear from the documentation. I’ve written about these three unusual yet anonymous individuals before, referring to them as the outside consultants, considering how they had been pressed by the court of Herod. The Magi may well have been diverted from their course, yet they knew enough of their senses of direction to keep on going. They most likely consulted with one another, determining not only what they would deliver to the place of the Nativity, but also that they would subsequently and compassionately slip away without reporting to Herod. And back into the unknown they went, keeping all of us wondering through all the centuries since then. They took their shared experiences with them, perhaps recounting the adventures to others in locations unknown to any documentation. Searching for assurance and advocacy is undoubtedly humbling, no matter how much experience one may have. The status of this perilous journey remains uncertain. My way of pushing back against the current of misery is by proceeding straight through the unknowing.

perspective

Navigating productively and healthfully requires both a sharp focus and a conscious sense of distraction, as I’ve been finding. This type of discipline balances proactive thinking with an ability to defensively drive away from fear-feeding stimuli. Choosing in favor of one is often a choosing away from the other. My longstanding curiosity about current events news has had to be tempered into much smaller, nontelevised doses; being informed needn’t mean overdosing. Listening to the car radio the other day, I noticed the patchwork of staccato reporting bounce between traffic updates and the worldwide scrambling for cures. The pandemic has surely intensified the already tough juggle for perspective. My long-usual preset bouncing away from news to music is now more frequently a turning-off of the sound system altogether.

For decades, I’ve made my livelihood using all sorts of computer technology and applications. Being a cradle visual artist, I’ve always kept a metaphorical ten-foot pole between myself and what I’ve long called “lit screens.” Nowadays this may look like a demonstration of creative independence and privacy, but actually keeping that safe distance is part of how I can maintain my footing in a reality whose vital means include handwritten media, real books, the outdoors, and personal interactions. As with a great many, the recent couple of years have forced me into living and working through lit screens. During the intensity and constancy of having to do this at the outset of the pandemic, I noticed how the pain of eyestrain would last far into the nights. I had to acclimate to the absorption of numerous consecutive hours online. Another vivid memory from the sudden quarantining of spring 2020 was my struggle with sedentary life and habitually looking out the windows for signs of life.

As tempting as it is to use the lit screens more as ends than means, especially in these alienating times, I’ve learned to be all the more selective and contextual. When browsing becomes a game of caroming between shrill news coverage and the enviably fortunate lives portrayed on social media, that’s when I turn off the lit screen. Imagine pinging and ponging from fearsome news to unattainable careers, back and forth; such joyful scenarios for thoughts to dwell upon! As a remedy, I’ve trained myself to look up from the lit screen, as I tell myself. Look up and around, even if means noticing dusty surfaces on the furniture. Looking up is a way to make note of your context- of where you are. It’s the equivalent of twisting that zoom lens back into a wide-angle, and try to get a bigger picture of the immediate. Looking up from a digital terminal is an indoor and admittedly modest version of being able to get outdoors to see horizons.

<

Perilous journeys cause us to cherish understated treasures we used to overlook. In this thinking, memory and hope converge. Remembrance helps us to look forward, while contending with present perils. While fine-tuning ways of waving off negatively distracting encroachments, I’m also deliberately creating distractions to send my thoughts into more positive directions. In yet another ancient text used for Advent, Saint Cyprian encouraged readers to “endure and persevere, if we are to be perfected in what we have begun to be, and if we are to receive from God what we hope for and believe.” He added that our acts of compassion must be united with patience and perseverance. “Do not grow weary, or be distracted, or be overwhelmed by the temptation to give up in the midst of the patient pilgrimage of life.” Endurance must be carried through to nothing short of the end.

staying sane

Eclipsed by the obvious urgency of fatalities in the millions, medical and economic crises, the mental toll of the pandemic is yet to be fully known. The latter is profoundly felt by many. I know this, albeit writing from my ledge on this planet, soldiering on in my employment. As with following health news, it has become impossible not to notice articles posted and published daily about the commonly-known Great Resignation. Also referred to at The Big Quit, workers have been leaving their jobs during the pandemic at rate unequaled by any previous U.S. Department of Labor statistics. In August 2021, 3% of the workforce resigned their jobs. 55% said they were job hunting. Adding yet another revealing statistic, 20% of the global workforce say they are “actively engaged” in their employment. This means eight out of ten workers say they are disengaged, for any of many reasons, amounting to a massive reaction to lingering exploitation. All the surveying and tabulating were evidently prompted by trends that are most likely nothing new, but surely accelerated by an overspreading societal malaise due to the pandemic.

Amidst the currents of these times is a popular realization about mortality. Life is short. We can’t be certain of how much time we have left to be able to inspire others, let alone to be able to accomplish our procrastinated wishes. The same employers that have been calling their workers “expendable” have begun to appear rather expendable themselves. Hence the unprecedented numbers of resigning workers who have not lined up subsequent jobs. Income and physical safety are often at odds. How will they pay their bills? It’s bewildering to watch, but entirely understandable. The weary world aches for the plagues and social conflicts to end. Few have the luxury of respite. Apparently, we are to soldier on, collecting our shots as we trek the contagion minefields. Survival always needs a purpose, and in this case I still envision being able to look back upon these present times whenever that critical corner is turned. Seeking signs of improvement runs parallel to the search for better opportunities. Perseverance and vigilance cannot be permitted to be ground down by fatigue. Meanwhile, redeeming the time between obligations, I continue finding consolations while studying philosophical works from the early-Renaissance era. Groote’s motivating words from the 14th century remind me that trials are proving-grounds. His students heard this while they struggled for equilibrium in the howling wilderness of the plague in late-medieval Holland.

Now having to launch again into the murky waters ahead, the need to continue being propelled from within constantly intensifies. Writing materials that include blank books for subsequent thoughts, along with my filled rapiaria volumes of collected wisdom, serve to hold course. The lights of my studies have led to gratitude throughout these recent two years of hardship. In the persisting face of unrelenting futility, my better reaction is to return to the words of Saint Cyprian which I quoted above, about not being tempted into losing hope. Trusting faith asserts that what is immediately visible is neither all there is, nor all there will be. Even the Magi continue to remind us about envisioning beyond the present. But upon the current, the ground of momentary being, San Juan de la Cruz always pointed to the wellspring of Spirit. Somehow he was able to instill and reinforce this awareness within himself during his wrongful incarceration. Before, through, and in his post-captivity life, San Juan poetically emphasized union with God as the purpose for survival through all times and trials. In his jail cell, he scribbled words on a sliver of paper begged from one of the guards; the scrawled notes became his Dark Night of the Soul, which he completed after his escape and remains in print to this day, nearly 450 years later. In the thick of what was supposed to be a death sentence, he discovered what he later called “the delight of contemplation and union with God,” finding “guidance in the night of faith.” The immersion he described demands that the soul must proceed by unknowing to unify with Divine wisdom. Surely speaking from indelibly physical and as well as spiritual experience, San Juan de la Cruz added, in The Ascent of Mount Carmel, that the soul has to...

“...proceed rather by unknowing than by knowing; and all the dominion and liberty of the world, compared with the liberty and dominion of the Spirit of God, is the most abject slavery, affliction and captivity.”