“For me, reason is the natural organ of truth;

but imagination is the organ of meaning.

Imagination, producing new metaphors or revivifying old,

is not the cause of truth, but its condition.

It is, I confess, undeniable that such a view indirectly

implies a kind of truth or rightness in the imagination itself.”

~ C.S. Lewis, Bluspels and Flalansferes

Giving lectures and reading to audiences have evolved into very comfortable and pleasant experiences. My teaching background certainly helps, but knowing my topics frees me from excessive rigidity. Obviously, it all depends upon the audience, and no two groups are ever alike. A recent presentation about archives lent itself especially well to some storytelling. On that particular afternoon, during a dreary winter day, I had brought out examples of treasures such as rare books, maps, prints, and city directories. These types of artifacts are especially conducive to time-traveling musings. I’m surely with the patrons, students, and all the curious- as we all marvel at photographs of specific places then-and-now, noticing the changes.

To do justice to my occupation, I taught myself about when certain various prominent buildings were built, extended, or demolished. Such facts continue to be invaluable for identifying undated imagery and supporting researchers. Years ago while sleuthing out the sites of extinct streets, writing narrative essays with an expression I coined: “ghost streets.” This is to say buried thoroughfares that are gone without a trace. These have been very popular. In a juxtaposition of past and present, cheering an audience on an especially damp day, I made reference to how the local art college is currently in a former department store building constructed in 1904. The store was called Porteous, Mitchell, and Braun (that first name is pronounced “POHR-tchuss”).

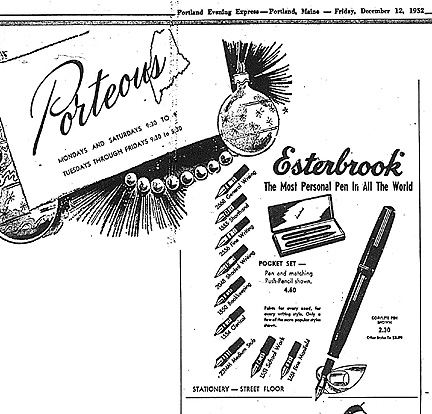

“Now imagine,” I offered to the group, pointing to my left, “walking up Congress Street, stepping inside that big building at number 522, and suddenly noticing bright chandeliers, colorful merchandise, the din of chatting salespeople and customers above the muffled piano music, and the aromas of cosmetics and perfumes.” There followed memories of people among my audience, chiming in with their own recollections. I held up a Porteous ad for Esterbrook fountain pens, printed from a 1952 Christmas season issue of the Portland Evening Express (which gave me a chance to explain the microfilmed newspaper collection). I am often in the role of informing patrons about what was, en route to explaining what is.

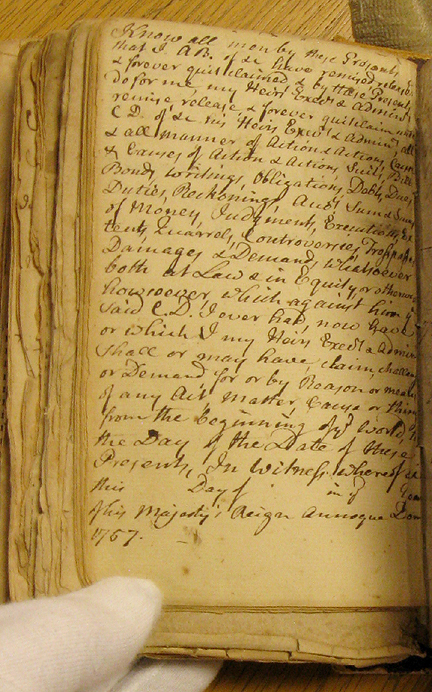

Early 20th century archival theorist Sir Hilary Jenkinson taught that archivists do best to read the documents in their care, and to be acquainted with the contents. I’ve personally seen this to be an extremely useful idea, especially when it comes to the level of service I can provide, and how I draw together sources and researchers. It’s really about recognition and making connections. Like compassion, these are uniquely human abilities. I’ve been studying the materials, making notes, and committing many things to practical memory. Indeed, this has become the less-traveled road, but the relational touch is surely the most meaningful. Just as people are souls, archives are recorded activities that attest. Through the years of preserving and providing public access to archival material, by default I’ve also had innumerable occasions to be acquainted with many of the people who inquire and use these artifacts. Often, there are patrons who will show up daily for a stretch of time, feverishly nibbling away pursuing evidence of parts of their personal histories. I witness all ages seeking the past, looking for understanding and purpose. I’m no different. Each request is respected, never derided. So many among us simply want to know, then let the witnessing archivist be an eloquent accompanist. With the philosopher Blaise Pascal who pondered in writing: “I am astonished at being here rather than there; for there is no reason why here rather than there, why now rather than then.” Inevitably, archives are facts that can enchant the imagination. Once again, and along with my students and patrons, I’m affected, too. Frankly, I could never figure out why other archivists don’t write about their metaphysical experiences. Manuscripts, images, maps, ships’ logs, and even ledgers present much more than what superficially meets the eye. And then there are the interactive discoveries for researchers interpreting the records.

The preservation of the documental record is meant to inform the panoramas between planning ahead, as well as the fleshing out of historiography. Narratives abound in manuscripts, revealing human activities and communications. Indeed, we can understand the popularity of historic novels! And then there is reverie. Serving the public for many years, once in a while I’m asked by patrons marveling over century-old photographs of streets crowded with pedestrians and trolley cars, “Why can’t things go back to the way they were?” Many, many more people wish this without admitting so much. We imagine with our hopes; speaking as a New Englander in the local parlance: “So don’t I.”

From pinched and barricaded confines, imagination insistently pries at the horizons. Ambition is vital. Don’t expect anyone to remind you to flex your hopeful imaginings; we must know to exhort ourselves. Speaking for myself, I write my wishes and prayers as journal entries, often scribing them amidst woeful environments. Remember to dream forward: observe and read between the lines. What we see is not all there is. Our conditioned and compromised cultures reduce our palates to bland, surface bluntness. It is for us to challenge ourselves to think beyond what is “at face,” and cultivate our intellects. We navigate societies of documented hard numbers and literal databases, but the human-voiced manuscripts invite us into the poetry of metaphor. When I managed and facilitated the reference library in a Catholic college, I read the memoir of St. John XXIII in which he wrote of himself, “I am a songbird perched in thorns.” Such a powerful metaphor has never left my thoughts, and I’ve invoked it numerous times since.

The spheres of metaphor and allegory have always provided places of habitation for me, though perceiving through these lexicons can be a two-edged sword when I have to creatively translate for those who cannot interpret subtlety. Fulton Sheen once said, “Introspection requires a lot of humility;” helpful words for speaker and listener alike. I’ll occasionally use archives as metaphor with my philosophy students. Wonderfully diverse as they’ve always been, they refreshingly think and speak at multiple levels. Archival work is entwined with axiological applications- as principles of origin, function, and value are integral to stewardship. Examples help provide crossroads for abstraction and practicality to meet. These also provide runways for metaphysical flights of fancy. Pointing to historic maps and photographs, I’ll ask, “Do places have intrinsic memories?” We’d like to think so. In my helpless insomnia, I imagine being cradled on the waves, aboard a peaceful vessel. In my curatorial adventures, I found documentation from 1948 about a Friend Ship that was sponsored by the Maine Rotary, which brought 107 cargo tons of food and clothing to France. The ship, built in Maine, was called the Saint Patrick, and it crossed the Atlantic in eleven days. Pleasant thoughts of calm seas and noble ambitions. Keep on visualizing better times. As confining situations constrict, my imaginings of comforts, vastness, and possibilities intensify as antidotes. I’d like to think there is still time for improvement.

1 comment:

I throughly enjoy reading your post. I am also inspired by them too. Looking forward to future post.

Post a Comment